Changing The Way VCs Generate Deal Flow

Unpacking an interesting strategy that later stage firms are using to build future pipeline

Welcome to all the new subscribers that have joined us over the last week! If you haven’t already, you should check out my last article here:

If you like what you read, please subscribe to Superfluid here:

It’s been a busy week, so this piece is shorter than normal. In my pursuit of making the venture capital industry more transparent, I share some tidbits and unpack the fund dynamics behind a recent shift in VC portfolio construction and capital deployment that I’ve observed. Hope you find it useful!

As a VC, I reject numerous companies every week. It’s probably the worst part of the job.

However, it’s always pleasing and exciting to see some of the companies that I’ve rejected for funding release a fundraise announcement a few weeks/months later.

It's always interesting to see who was able to get enough conviction to invest and figure out what they saw in the company.

Recently, I came across a company that I had passed on that ended up getting funded by a few smaller funds and then 1 large fund. With a bit of sleuthing, I found that the large fund wasn't the lead investor and didn't invest that much into the round.

I also found out that they were actively looking to employ this strategy at scale and were specifically looking for seed-stage startups to write relatively small cheques into.

Whilst this isn't necessarily a red flag in its own right, it is an interesting deployment strategy.

Venture Capital Marketing Budgets

A venture fund typically charges a 2% management fee for 10 years of the fund's life.

The 2% fee is intended to be used towards administering the fund. That includes hiring staff to support the fund and administrative overhead charges (legal, accounting etc.).

As part of running the fund, this management fee is also put towards marketing purposes. VC funds are just like any other startup. They need to increase brand awareness of their firm and generate deal flow through different channels.

Typically, this is done through sponsoring events, running hackathons, and the occasional Michelin star dinner or open bar tab.

These channels are usually effective at bringing in lots of unqualified deal flow. You get bombarded by pitches which is a good thing, but unfortunately, also require a lot of effort to go through and are sometimes dubious in quality.

However, the best marketing strategies are when you can put $1 into it, and come out with $3 at the other end. From the perspective of a VC fund, the ideal outcome is that every deal sourced through a channel is high quality and investible.

In this instance, the fund in question is using a portion of its investible capital as its marketing budget. By doing so, they can heavily qualify their future pipeline by already being on the cap table and having an informational advantage ahead of the next round.

As we’ve spoken about before, the business model for large funds is to deploy lots of money and raise larger funds in quick succession. For large funds to continue staying large, they need access to deals that can ingest a lot of capital in a short amount of time.

In 2021, the standard approach here was to move earlier in the capital stack and deploy lots of money into seed stage businesses that couldn’t responsibly use that capital. We’re seeing the outcome of this approach at the moment with many companies struggling to find Product-Market-Fit despite having millions in the bank.

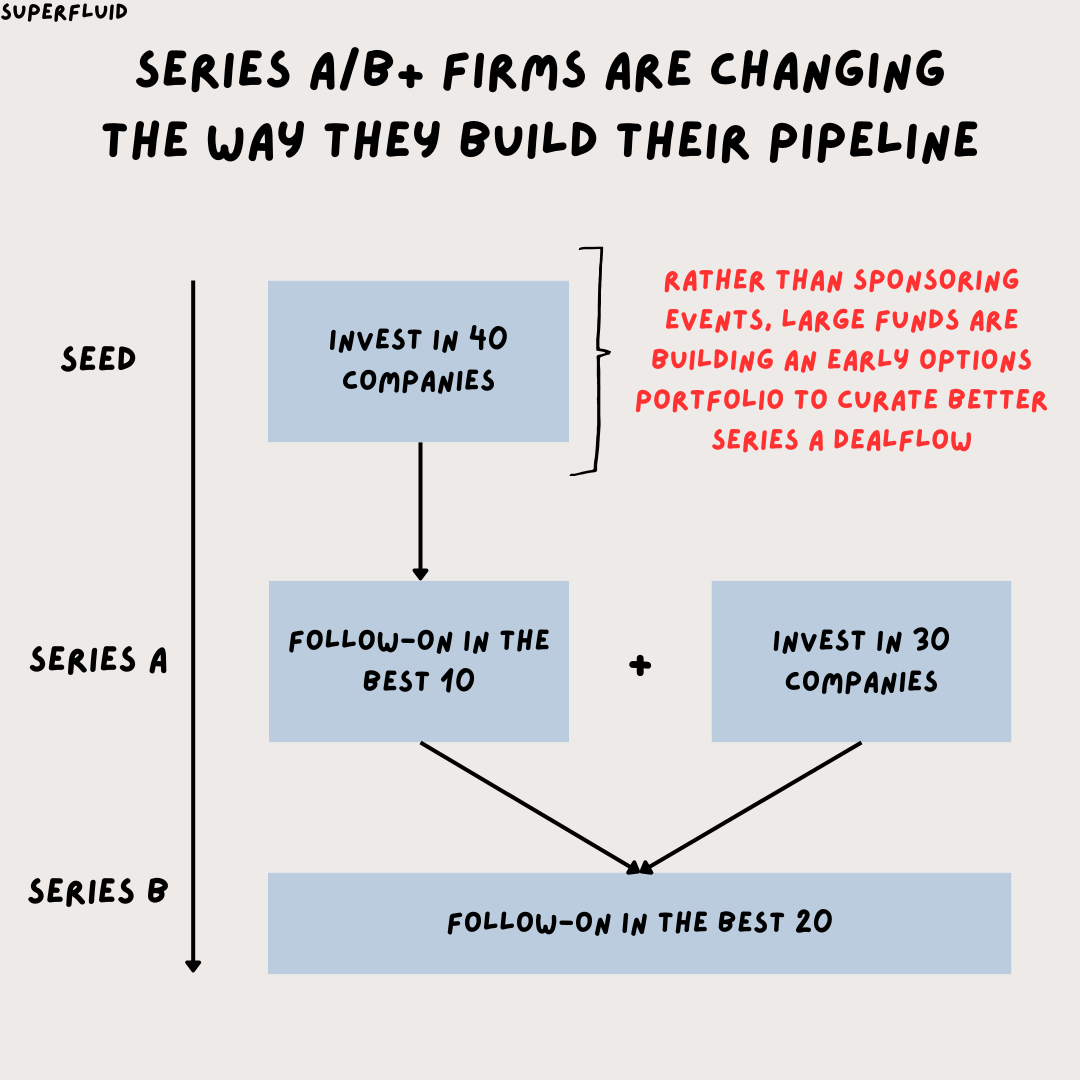

And so, instead of leading Seed rounds with $5M cheques, this particular fund is following into Seed rounds with cheques under $1M. These cheques are effectively meaningless in the context of the fund’s size, however, give them the opportunity to curate their pipeline better and deploy large Series A cheques into strong companies.

As an example, by investing in ~40 seed-stage companies, they are probably hoping that 8-10 of these businesses fit that profile. Once these winners emerge, these funds will also probably invest a higher-than-average amount into the Series A, given their downside is somewhat derisked through having an informational advantage.

Effectively, this strategy is trying to scale the traditional scout model that VCs have used for decades. Traditionally, VCs would give talented entrepreneurs, founders and other ecosystem participants a 10 - 50K cheque to deploy into any company they wanted to invest in usually at the angel/pre-seed round. In this case, large funds are effectively running their own in house scout programs rather than outsourcing it to someone else.

By doing so, this comes with its on pros and cons for both fund and founder.

What Does This Mean for Founders?

For founders, this can be a good and a bad thing.

First and foremost, you need to acknowledge that they don't care about your business yet. At this point, your business is just another deal to them. If you do well, then you’ve probably got your next round sorted without having to do much work. If you don't, then their investment is just the cost of doing business for them, and a wasted slot on the cap table for you.

If you want an investor to care about you, then you need to make them properly aligned to the success of your business. The best way to do that is by making sure they deploy a meaningful portion of their fund into your business. A good threshold for this is about 2 - 4% of the fund.

In addition to this, think about the fund's return hurdles, and calculate the terminal value that you need to achieve to return the fund for them. For small and medium-sized funds, this threshold will be lower given they have a solid ownership stake in your business.

On the flip side, big funds only care about big outcomes. They need to own a solid chunk of your business (10%+) AND need you to achieve a big outcome for it to be meaningful to them.

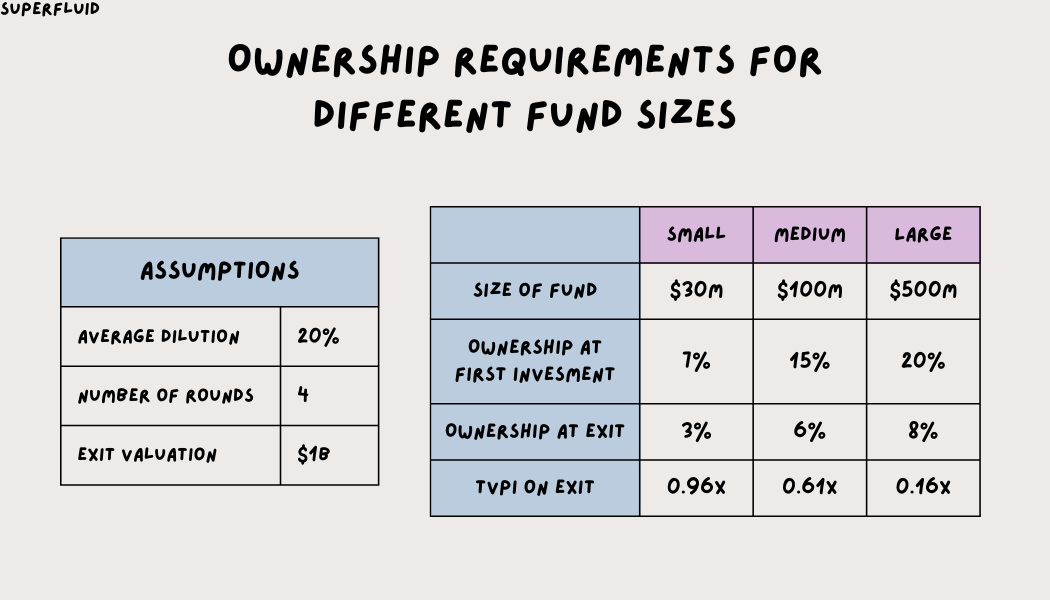

In the diagram above, I’ve assumed that the company raises four rounds of additional rounds of capital and takes on 20% dilution with each round before exiting at a $1B valuation.

On the right-hand side, I’ve also made some fund-specific assumptions, around the initial ownership stake that each fund type would be looking to take. 7% for small funds, 15% for medium and 20% for large funds. This scenario does not account for funds making follow-on investments into the company.

From the table on the right, you can clearly see that the small fund can basically return the fund with just 3% ownership at exit. On the other hand, the large fund can only return 16% of the fund with 8% ownership at exit. In reality, a large fund will maintain its pro-rata as long as possible and negate the impact of dilution.

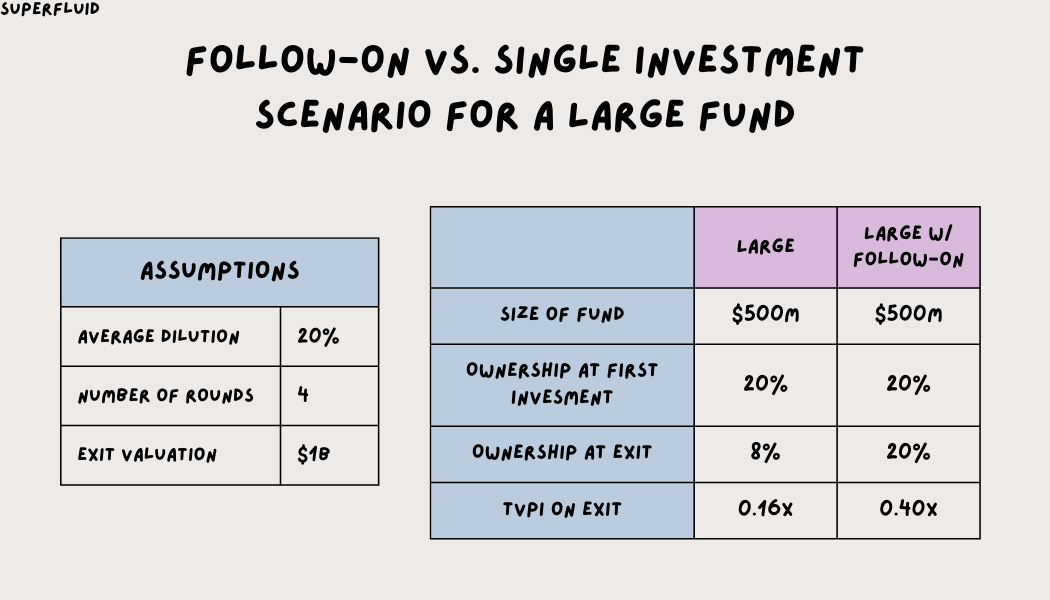

Even in the instance where a large fund can maintain its 20% ownership stake, that still results in a single investment TVPI of 0.4x. In fact, the company needs to hit a $2.5B valuation for it to return a $500M fund.

So if that’s what it takes to return a large fund, it’s clear to see the incentives at play when a large fund deploys a small cheque into a seed stage company. It means everything to you to have them on your cap table, and nothing for them in the context of their fund.

Once you understand this, my advice to founders is to do the following:

Push them to invest more in the round - the larger the check from them, the better. There are a few levers you can pull to get them to invest more. The first thing you can try is by telling them you don't want too many investors in the round, and that you want them to fill out whatever the lead investor can't do. For example, if the round size is $3M and the lead investor is willing to do $1.75M, the large fund might only want to do $250 - 500K. Instead, you should give them an ultimatum - either they fill out the round or they lose their allocation. This will test whether they are willing to back you and your business, or if they're just buying an option.

Get them to be helpful before they invest - test whether they will be helpful and whether they care about your business before they invest by asking for intros, strategic advice etc. before the money hits the bank. If they follow through on their promises, that's a good sign. If not, then you know to stay away from them.

To reiterate, having a large fund with a small position on your cap table is not an immediate red flag. If things go well, then you have a dependable source of capital for the next round. You also have access to a large platform that could be helpful.

However, you also need to be aware that it can hinder follow-on funding if they don’t follow on or only do their pro-rata. It also isn’t a great signal if you’re looking for a lead and have a large fund waiting to follow. Make the right decision in the context of your business and remember that Cap Table-related decisions are nearly impossible to reverse.

Make sure to subscribe now to not miss next week’s article

How did you like today’s article? Your feedback helps me make this amazing.

Thanks for reading and see you next time!

Abhi