So, is it Venture scale?

Diving deep into what being Venture scale means, and why this is even a question

Welcome to all the new subscribers over the last 2 weeks! You can read my last article on the creator economy here.

Stay up to date with Superfluid by subscribing here:

“So, how is this a Venture scale business?”

As a VC, this is a question that inevitably comes up when looking at a new company.

Most of the time, the answer is negative.

Venture Capital funding really only applies to a small subset of businesses. And to clear this up early, you can absolutely be successful without raising a single $ from a VC.

But in a world where a canned water company raised $75M in a Series C round and is valued at $525M, what does being Venture scale actually mean?

Why do VC’s obsess over being Venture scale?

Before we dive into it, let’s take a step back and run some quick calcs.

VCs invest money on behalf of their Limited Partners (LPs). These LPs are typically High Net Wealth individuals, Charities, Super/Pension Funds and other institutional investors.

These investors have various asset classes and investment options to allocate their capital. When they allocate their money to a VC fund, they expect at least a 3x-3.5x return on this capital. I.e., If they invest $1M, they expect to see at least $3M-$3.5M returned gross of fees.

So the average VC fund might raise $50M meaning they ultimately have to make at least $150M to satisfy their LPs. To make the $150M, they might invest $1-2M into ~25 startups. This means that each startup would need to return at least $6M to the investor.

However, in 2021 funds raised more capital than every before, are were pushed to invest in larger rounds culminating in a $350M ‘pre-seed’ round led by a16z into Adam Neumann’s company Flow. For the most part, this level of funding whilst positive in the short run for founders is largely detrimental to the long term prospects of most companies.

Whilst probably outside the scope of this article, raising larger rounds, leads to higher valuations which means more pressure for the business to grow faster by the next round. We’re starting to see the effects of startups operating in tough markets really struggling to raise an up or even flat round in 2022 after raising a ton of cash in 2021 due to not growing fast enough or having enough traction to raise another round.

Combined with the fact that startup success is not normally distributed, typically following a power law distribution, we’re likely to see a bunch of companies burn through a ton of capital with nothing to show for it.

VC funds hope that across their portfolio, they have a handful of strong outliers to make up for the failures. The flow-on effect of this is that each company in a VC portfolio needs to have the potential of returning at least the full fund if not 2x the fund. With greater capital deployed in a startup, exit valuations need to grow proportionally or better yet, exponentially to this.

We’re likely to see higher exit valuations over time, but I expect this will only apply to the very best companies. Ultimately, as funds grow larger, the barrier to becoming a Venture scale business increases.

Defining ‘Venture Scale’

So now that we understand the requirement on VC funds to return a multiplier on their invested capital, how do they actually decide whether a business is Venture scale or not?

Large Addressable Market - Usually the first filter an investor might apply on a startup is whether the startup is solving a problem in a big market.

Whilst there is a lot of conjecture around whether calculating a TAM for a startup is a valid approach - it’s useful in understanding the state of the market right now, and thinking about the possibility of the market expanding through the permeation of said startup’s product over time.

However, VCs might quickly dismiss startups from receiving funding due to not tackling an obiously large market. Moreover, VCs might dismiss startups where the market is big, but not big enough in the context of their fund size and return requirements (see aforementioned comments on the necessity to deploy more capital and the requirement for higher exit valuations).

On the founder’s side, the onus is on them to be able to craft a compelling narrative for their business. They need to be able to show unique insight that is able to convince VCs that the market is bigger than what they might think and why it will expand rapidly in the coming years.Pathway to becoming a Monopoly — Big markets are only good if you can capture a significant portion of them. The best markets are non-competitive and market domination in a category gives companies pricing power and the ability to outlive their competition.

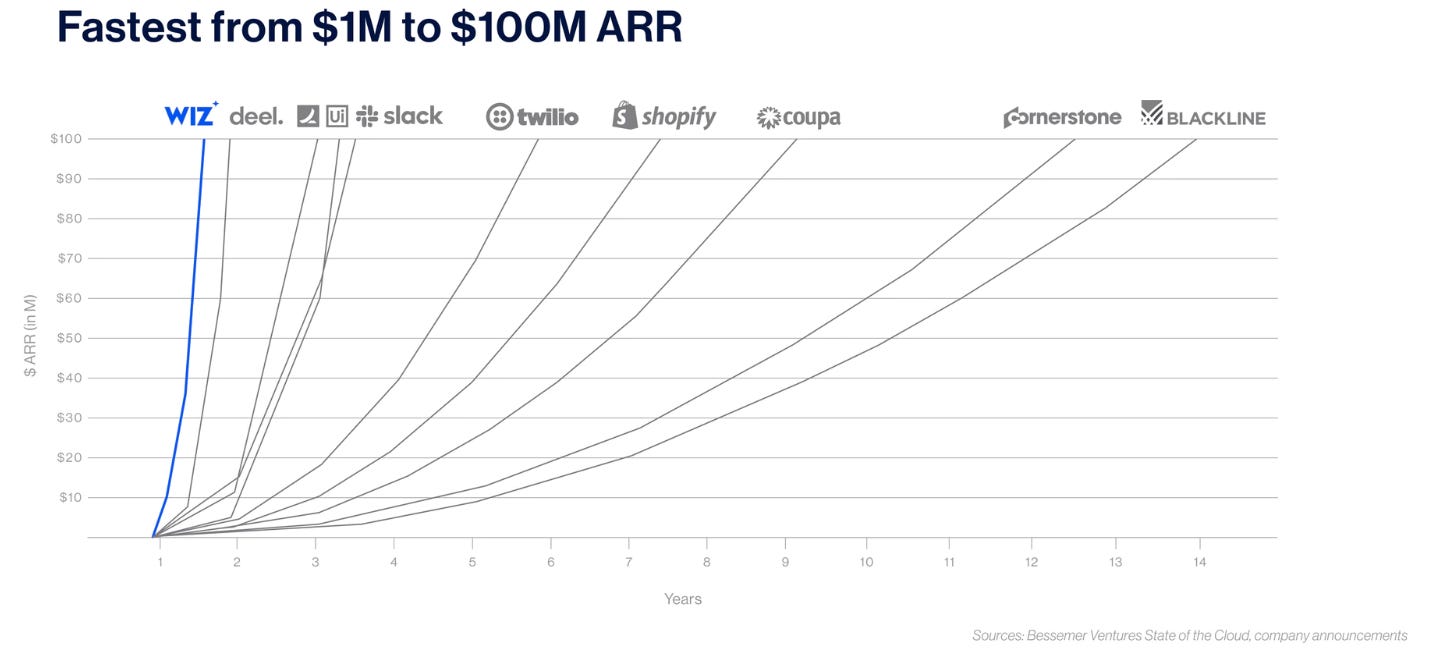

If there is a ton of competition in the market a startup is building in, this immediately causes VCs to hesitate and deliberate whether the business will be able to truly scale to $100M+ in revenue which has become the defacto rule of thumb for VCs globally to define a $1bn business.

Whilst the $100M ARR rule has flexed in recent times with extreme multiple expansion through 2020 and 2021, it serves a solid benchmark for most SaaS businesses. Founders should understand the pathway for their business to hit this revenue target through a realistic forecast of their customer acquisition and demonstrate how Average Contract Values or Average Revenue Per User might expand over time.Blitzscaling potential — One of the conditions for taking investment from a VC is that the startup needs to be able to grow ridiculously fast. To be able to conquer a large market, they need to be able to ship product quickly and grow their user base and by association their revenue exponentially.

Deel had a short reign as the $100M ARR king, hitting the milestone in April 2022, before being overtaken by Wiz in August 2022 VCs typically use the ‘Triple Triple Double Double Double’ (T2D3) framework to assess whether a SaaS startup is showing signs of hypergrowth. Once a startup has hit ~$2 million in ARR, they have a ticking clock for them to hit the $100M milestone. In year one, they need to triple revenue to $6M, year two - triple it again to $18M, and then double it continuously for the next three years registering $36M, $72M and $144M respectively.

This level of growth is strange and unnatural. Most businesses shouldn’t be subjected to this level of pressure. Many markets also can’t handle this level of growth. As a result, if the path to pulling off T2D3 is somewhat unclear it gives VCs a reason to pass on the startup.

Does being ’Venture scale’ matter?

Whilst we’ve covered a few ways to think about what Venture scale might mean, there is no universal definition. Every fund, and investor will have their own opinion on what this means.

To combat this as a founder, you should be able to communicate why you are playing in a large and valuable market, as well as why your business has the right to win. A VC investor will never have the same level of insight into a market as a founder, which means that the onus is on the founder to craft a narrative that is so compelling that being Venture scale is never a question.

Make sure to subscribe now to not miss the next article.

How did you like today’s article? Your feedback helps me make this amazing.

Thanks for reading and see you next time!

Abhi