The Early-Stage Conundrum: Good vs. Great

The goal of venture capital is to fund great businesses and not good businesses

Welcome to all the new subscribers that have joined us over the last week! If you haven’t already, you should check out my last article here:

If you like what you read, please subscribe to Superfluid here:

The goal of venture capital is to fund great businesses and not good businesses.

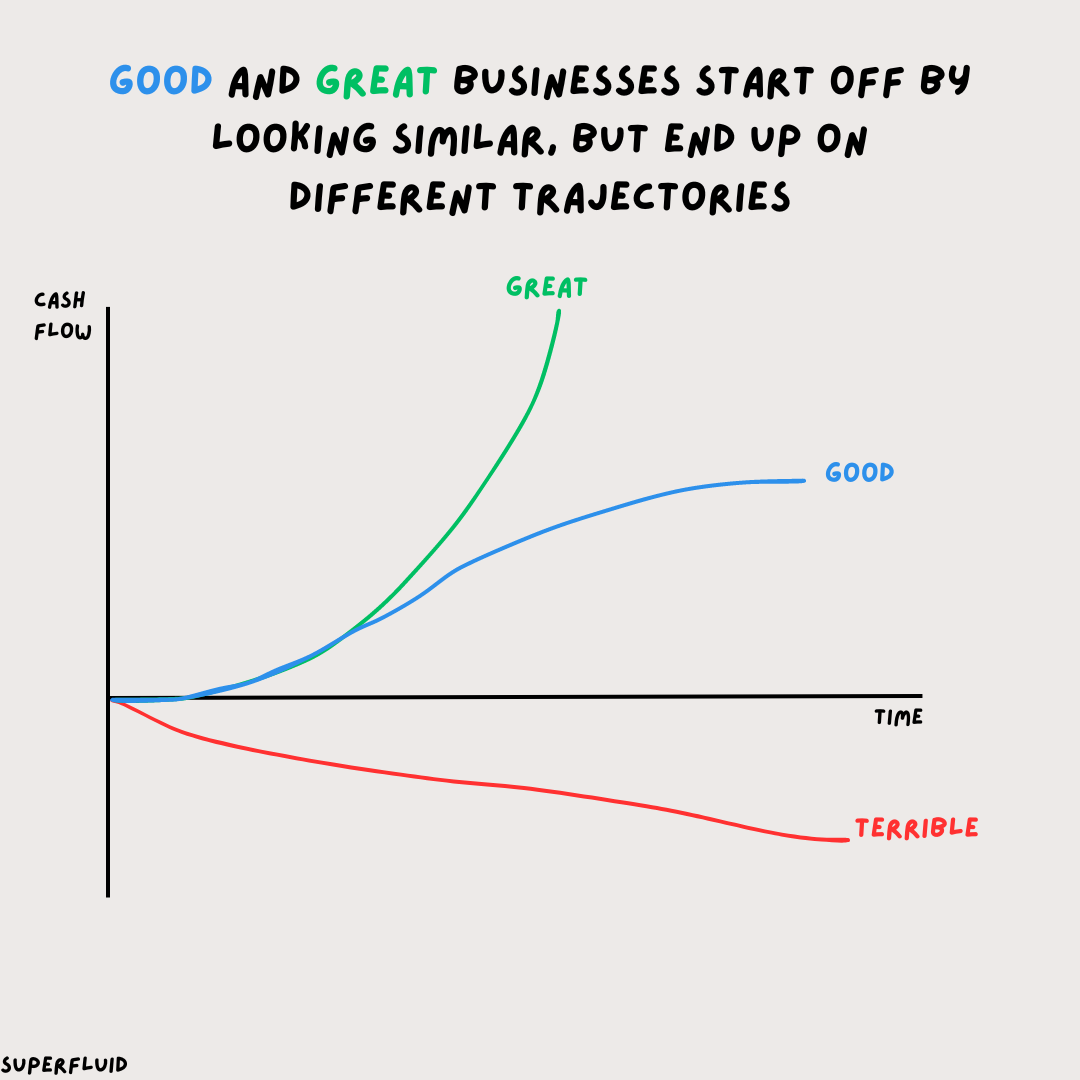

However, at company inception, it's not clear whether a business is great, good or even terrible. As a result, VCs invest in a lot of businesses that are either good or terrible - this is a direct result of playing the power law game.

Identifying a terrible business is straightforward. These typically have poor unit economics, where the cost to generate revenue is disproportionately high – for example, spending $4 to earn just $1. Moreover, their growth often demands substantial capital without yielding any significant product or distribution advantages

The distinction between good and great businesses is more subtle and nuanced.

A great business (in a VC context), ingests capital at scale, uses said capital to scale at an insane growth rate and compounds its advantage over other competitors continuously. These businesses have $10bn+ outcomes that are good for both founders and VCs.

Similarly, a good business is one that grows linearly and is increasingly cash flow accretive. These businesses should not raise a lot of external capital (ideally 1 round) and instead use their cash flows to sustain growth. If a company is in this bucket and raises too much capital relative to its potential, then founders lose out on their ability to have a strong personal exit (i.e., many millions of dollars).

The nuance between the two is apparent when a company is just starting to grow. There will be periods where growth is exponential, linear, flat and everything in between. With limited information, it's hard to tell whether a company will be a good, stock-standard business or whether it'll be the next Google. Early-stage companies always have problems, it's incredibly rare to see a business face little challenges as it scales.

The Funding Conundrum

Herein lies the conundrum.

Venture capital is optimised for early seed bets, and perfect for doubling down on great businesses. However, it will undoubtedly suffocate and destroy good businesses with too much capital. This is by far the biggest disservice VCs are doing to founders at the moment.

Over the last 18 months, VCs have been triaging their portfolios, encouraging founders to push towards profitability, and helping them with bridging rounds to give them more runway to hit stronger milestones. Founders are willing to raise capital with predatory terms all in the hopes of staying alive and with the belief that they are still on the pathway to becoming a great business.

I think it's reasonable for founders to think this way, and you do need a healthy level of delusion to be able to build a great business. However, I think many founders don't necessarily consider alternatives that well. It takes a mature founder to think introspectively about their business and figure out whether it makes sense to keep raising capital to keep the business alive.

Far too many venture-funded businesses believe that the extra capital will magically solve their problems, and 1% of the time, the extra capital might allow the business to stay alive, just long enough to capitalise on a tailwind that sends the company to stratospheric heights. For the other 99% of cases, once you raise with predatory terms or if you raise too much money, the margin for error is slim if the founder wants to make any money at all.

So what happens to these businesses?

At the moment, we have three contenders for businesses that could be good:

Businesses that are already profitable, but growing under 10% MoM

Businesses that are not currently profitable and are limping their way towards break even

Businesses that are burning cash with no change in fortune in sight. These companies will run out of cash within the next year

Category 3 is the easiest one to deal with - either look to exit or close up shop. If there is no clear catalyst in sight, there is literally no point in trying to prolong the inevitable. If there is still conviction in the market and product approach, it's better to take the IP and assets built so far and roll that into a new structure with new investors rather than continue with a broken cap table.

Businesses that fit the profile of Category 2 are in a tricky spot. These businesses might have a decent shot at hitting breakeven with the cash they have in the bank, but what happens after that? Do they raise further capital and try to grow exponentially again? Do they try and make do with the cash flow that's in the business and grow using that? Or do they position themselves as an acquisition target?

I'd say all of those options are on the card IF the business can get to breakeven. However, I think it's probably unwise to contemplate raising capital unless there is something fundamentally different with the business or there is a strong growth catalyst on the horizon. In saying that, I'm currently seeing a crop of companies trying to raise a bridge round to get to profitability. The problem here is that many of the founders in this bucket think they are category 2 companies, but instead are actually category 3 businesses, with low to no future growth prospects.

Instead, founders would probably be better off positioning for an acquisition, if they aren't willing to keep grinding away at building the business. This way, they might have the backing of a large strategic partner who can help with some of the hard stuff in the business. Of course, the caveat here is that the founders will need to work for someone else for at least their earn-out period, which most founders don't really want to do.

Category 1, is clearly the best, but also the easiest to screw up. With Category 1, there is a temptation for founders to look at their growth rate and think they can accelerate with additional capital. Instead, the better option is to actually sit back and reassess the opportunity. If there is a clear growth catalyst, and one that requires a substantial amount of capital, then go ahead and raise a round of capital. If there isn't anything that requires a lot of money, then it's better to recycle cash back into the business and build a war chest for future use. By not raising money unnecessarily, founders will protect their ownership stake in the business. This allows them to either position the company for acquisition when the time is right or issue dividends back to investors and other stakeholders.

What's the point of venture capital?

The above sounds pretty doom and gloomy - is there any point in raising venture capital?

The goal of a pre-seed/seed round is to figure out whether a business is good or great. Determining this involves derisking the right things (see article here), and figuring out whether the market and product dynamics are aligned towards building a great business (definition above). The quicker a founder can figure this out, the better they can optimise for their chosen pathway.

As a VC I am obviously biased in this regard, but, I think I am more open-minded than most. Ingesting capital from a VC fund is only suitable for a thin sliver of businesses and comes with strings attached. At the pre-seed and seed stage, it's important to maintain optionality with regard to the path a startup takes.

The easiest way to do this is by choosing the right aligned investor. This is different depending on the initial capital requirements for a business. If you're looking to build an AI foundational model from scratch, you probably need to raise a pretty hefty round - you'll only be able to do this from large multi-stage firms that can write a large enough check. If you're building a standard SaaS business, I think it makes more sense to raise from a smaller VC that has lower return hurdles (again, I'm biased as Rampersand is a small-mid-sized VC fund).

As an aside, I hope that this period of reckoning for startups allows for more fund model innovation for VCs. There are so many types of businesses that are poorly served by the existing fund model. If we're truly going to solve for diversity and inclusion within startups and venture capital, then we need diversity amongst different fund models. If you're interested in hearing my thoughts on this, either comment below, or shoot me a quick email saying so!

Make sure to subscribe now to not miss next week’s article

How did you like today’s article? Your feedback helps me make this amazing.

Thanks for reading and see you next time!

Abhi